Huntley’s Connection to the Iroquois Theater Fire

Huntley’s Connection to the Iroquois Theater Fire

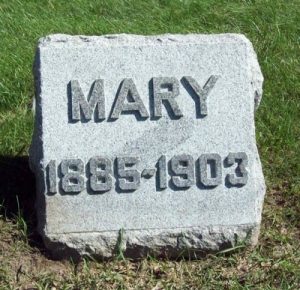

In a small, unremarkable grave in St. Mary Cemetery in Huntley, a tragic story is buried.

It is the tale of 18-year-old Mary Donahue, the granddaughter of early Huntley settler Daniel Donahue and Huntley resident Bridget Heelan.

Over the Christmas holidays in 1903 Mary and a girlfriend arranged to attend a performance of the musical Mr. Blue Beard at the newly-opened Iroquois Theater in Chicago.

The December 30 matinee hosted a sold-out crowd, with several hundred Standing Room Only spots sold at the back of the upper floor.

Shortly after the beginning of the second act, with Mary and her friend sitting enthralled in their seats, sparks shot out from an arc light overhead and ignited a muslin curtain. The flames spread to several thousand feet of canvas scenery hanging in the rafters. The stage manager dropped the asbestos fire curtain, but it snagged on its way down and was stuck.

The fire spread quickly. Patrons attempted to flee to safety, but fire exits were hard to locate. Those who did locate the exits found they had odd locks on them that could not be opened. Most tragically, the theater doors opened inward and the crowds pushing from behind made the doors impossible to open.

Mary Donahue was amid the mayhem as everyone tried to flee to safety.

Ultimately, more than 600 patrons died in the fire and several hundred more were injured.

Fire codes, fire safety and building construction regulations were changed dramatically because of the heartbreaking catastrophe.

Among the changes were the requirement that exit “crash doors” open outward. Fire alarms and sprinklers were required in all public buildings. Exit signs were to be lighted and clearly visible, and “standing” tickets were eliminated.

All came to late for Mary Donahue.

This fire resulted in federal and state standards for fire safety including:

–Clearly marked and lighted exits

–Exit doors to open outward with panic bars

–Mandatory fire drills for staff

–Emergency lighting

–Fire alarms required

–Standing Room Only seating banned

–Sufficient fire extinguishers required

–Stairways must be clear and open